Body and Soul

__________________________

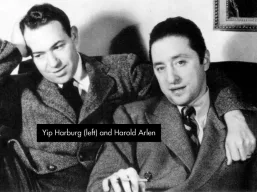

Body and Soul (m. Johnny Green, w. Edward Heyman, Robert Sour, Frank Eyton)

Jack Hylton and His Orchestra were first to record the song, in Great Britain. Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra soon followed with a hit recording in the US.

Jack Hylton and His Orchestra were first to record the song, in Great Britain. Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra soon followed with a hit recording in the US.

Excerpts from WICN.org’s “Song of the Week” feature:

It’s hard to overstate the influence “Body and Soul” has had on jazz. It probably is the most recorded of all jazz songs, with nearly 3,000 versions to date, and new versions continue to proliferate. Tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins’ 1939 version of “Body and Soul” established it as the leading jazz ballad for instrumentalists, and it remains the acid test for tenors. Hawkins’ recording often is credited with establishing the tenor saxophone as the major jazz instrument. Before that the trumpet dominated jazz, thanks in large part to Louis Armstrong. “Body and Soul” is the archetype of a torch song and singers ranging from pop stars to hard core jazz vocalists have used it to display their range and improvisational abilities.

As has often been the case with other celebrated jazz standards, “Body and Soul” had a modest birth. Johnny Green, its composer, was frequently asked if, when he was writing “Body and Soul”, he knew it was going to be the most recorded torch song of all time. His set response was “No, all I knew was that it had to be finished by Wednesday.” Along with lyricists Edward Heyman and Robert Sour, he wrote the song at the request of Gertrude Lawrence, an English actress specializing in musical comedy, who was in need of new material that included a torch song. Heyman came up with the song’s title. In February of 1930 the song was copyrighted first in England and Lawrence sang it on British radio but never recorded it. Thanks to the wireless, it became very successful and the most popular bandleader in Britain, Jack Hylton, made the first recording. Recordings by bandleader Bert Ambrose and other British musicians soon followed.

“Body and Soul” returned to its native country in the fall of 1930. It was to be introduced to the American public in a Broadway revue, Three’s a Crowd, starring a new talent, Libby Holman. In spite of its European success, the song almost didn’t make it to Broadway here. Holman objected to the lyrics and was dissatisfied with the orchestration, requiring both to be extensively reworked. At one point she became so upset with the staging that she threatened to walk out. At the last minute, the revue’s director came up with a new staging, in which Holman simply walked onto the stage in the classic torch singer’s slinky black dress and sang “Body and Soul.” That was all it took to make her a star and the show and the song immediate hits. However, the song still was not universally loved by the New York critics.

Libby Holman – 1930

.

See my comments at the foot of the page regarding an alternate, and greatly inferior in my opinion, lyric used in recordings to follow by Helen Morgan, Ruth Etting, Annette Hanshaw, and Louis Armstrong, all in 1930, and by Red Allen in 1934.

Helen Morgan — recorded 12 September 1930

.

Ruth Etting – recorded 29 September 1930

.

Annette Hanshaw – recorded 7 October 1930

.

Louis Armstrong and his Sebastian New Cotton Club Orchestra, recorded in Los Angeles, 9 October 1930

.

Henry “Red” Allen and his Orchestra – recorded 29 April 1934

Henry “Red” Allen and his Orchestra – recorded 29 April 1934

Henry Allen – trumpet, vocal

Dicky Wells – trombone

Cecil Scott – clarinet

Chu Berry – tenor saxophone

Horace Henderson – piano

Bernard Addison – guitar

John Kirby – string bass

George Stafford – drums

.

Benny Goodman Trio – 1935

.

Coleman Hawkins — recorded in New York 11 October 1939 (Bluebird 5717-2-RB)

musicians: Coleman Hawkins (tenor sax), Tommy Lindsay & Joe Guy (trumpets), Earl Hardy (trombone), Jackie Fields & Eustis Moore (alto saxes), Gene Rodgers (piano), William Oscar Smith (bass), Arthur Herbert (drums)

Alan Kurtz, in a review for Jazz.com, said:

Historian Ted Gioia calls this “the most celebrated saxophone solo in the history of jazz” and “a landmark, breakthrough performance” that’s been “studied by generations of musicians and is loved by countless jazz fans.” Of course, not every listener will care to analyze pedagogically a musician’s chordal navigation. Moreover, what Gioia describes as Hawkins’s “ponderous tone” and “baroque arpeggios” assembled in “rigidly logical” construction may strike today’s ears as mechanistic and old-fashioned. Even so, “Body and Soul” deserves its due. No trailblazer in tenor sax balladry cut a wider swath than Coleman Hawkins.

.

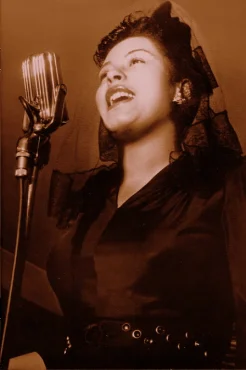

Billie Holiday — Session #39 – New York, 29 February 1940 – Billie Holiday & Her Orchestra (Vocalion) — Roy Eldridge (tp) Jimmy Powell, Carl Frye (as) Kermit Scott (ts) Sonny White (p) Lawrence Lucie (g) John Williams (b) Harold ‘Doc’ West (d) Billie Holiday (v)

.

Art Tatum – two versions, 1940 and 1953

.

Hazel Scott — V-disc no. 68 from 1943. The B-side side is C Jam Blues recorded by Hazel Scott and Sydney Catlett, though I’ve been unable to verify the date given in the video, 27 August 1943

.

Billie Holiday – Live session #15 New York 12 February 1945 — Jazz At The Philharmonic (Clef) — Howard McGhee (t), unknown (tb), Willie Smith (as), Illinois Jacquet, Wardell Gray and/or Charl[ie] Ventura (ts), Milt Raskin(?) (p), Dave Barbour? (g), Charles Mingus (b), Dave Coleman (d), Billie Holiday (v)

.

Frank Sinatra — recorded 11 September 1947 at Columbia Studios; arranged by Axel Stordahl

.

Anita O’Day with the Russell Garcia Orchestra — recorded in Los Angeles in September 1958; issued on the LP Anita O’Day Sings the Winners (Universal 9283)

.

Wes Montgomery – recorded 12 October 1960 at United Recording Studios, Los Angeles, CA and released on Movin’ Along, 1960 — Wes Montgomery (guitar, bass guitar), James Clay (flute, tenor Sax), Victor Feldman (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

.

John Coltrane – from the album Coltrane’s Sound, recorded 24 & 26 October 1960, Atlantic Studios, New York, released 1964

- John Coltrane: sax, soprano & tenor

- Steve Davis: bass

- Elvin Jones: drums,

- McCoy Tyner: piano

.

.

Coleman Hawkins – Jazz at the Philharmonic, London (BBC) – 1967

.

Bill Evans Trio and Toot Thielemans – Affinity, 1979

.

Kenny Burrell & Tommy Flanagan – Japanese TV, 1991

.

Apr 20, 2012 @ 11:50:17

Wonderfully useful site for my students, thanks! An obvious question, why no recording of Hawkins’ 1939 version, the most famous by far?

LikeLike

Apr 21, 2012 @ 12:47:28

Eric, Hi. Not sure why that was omitted. It may have been unavailable at the time I created the site. I plan to revise the page considerably.

The song is not a favorite of mine, though I recognize some of its influence through the numerous borrowings from and imitations of its melody and middle eight in subsequent early 1930s songs. There is an inferior lyric used in certain early versions which may have been (I speculate) introduced as replacement for the original after recordings of the song were, according to jazzstandards.com, “banned from radio for nearly a year because of its suggestive lyrics.” This second lyric version is not a case of tweaking the original to make it more singer-friendly or to appease radio advertisers and watch groups. We’ve got a completely new lyric. Every line is different, though a couple of them are similar to lines in the original. I’ve not yet determined who wrote it. Frank Eyton seems a likely suspect as he wasn’t one of the original lyricists working with Johnny Green, but according to a fine article on the song titled What’s in a Song: Body and Soul by John at his blog Running After My Hat, Eyton’s credit may have been payment for smoothing the song’s entry into a recording studio in England.

Vocalists who used the alternate lyric include Helen Morgan, Ruth Etting, Annette Hanshaw, and Louis Armstrong, all in 1930, and Red Allen in a 1934 recording. Was the entire second lyric a sham or was it tampered with by an amateur or two? It’s mainly an unspired, melodramatic collection of cliches. But my attention is drawn to the second half of the following section:

The second couplet, with the unaccented ending of “abandon” paired with the fully accented last syllable of “had planned on,” is striking, especially considering the fact that the song is routinely recognized as among the best of the elite as standards go. Ordinarily, this would have been considered sloppy or lazy writing in the classic American Songbook era. It’s not even a decent off-rhyme, since both the pronunciation of and the stress upon the final syllable of the first line of the couplet is different from that of the second. Nevertheless, it works reasonably well in practice. Singers do not try to rhyme the two last syllables, the rhyme is limited to the single syllable “-and,” and the difference in the final syllables provide a not unpleasant variation. Still, I believe the best songwriters of the era would have rejected such a construction outright.

Furthermore, “this abandon” means what, exactly? According to freedictionary.com, the noun “abandon” means

1. Unbounded enthusiasm; exuberance.

2. A complete surrender of inhibitions.

You can shout, drink, play, or party with abandon. But try to express sadness enthusiastically, or to sink into despair with abandon. True, there may arise moments when one is compelled to express grief with loud, unrestrained sobbing or wailing, and the like. Throwing things. However, in none of the vocal versions I’ve heard does the tone of the singer remotely approach a point what might be termed a wild or uninhibited quality, or suggest such an emotional state.

Of course, eighty plus years ago the word may have had other connotations. Used as a noun, in the way illustrated above, abandon may have suggested a state of abandonment of hope. However, I have never come across another instance of it being used precisely this way, where someone or something has been “left in (this, that, or the other) abandon.” In Google searches of the phrase “left in this abandon” the results consist of sites quoting this second lyric, and a line from the short poem Umbra by Alexander Pope, first published in 1727:

Poor Umbra, left in this abandon’d pickle

“Abandon” is not used as a noun in the Pope line.

Perhaps whoever wrote the phrase in question had “this abandonment” in mind, but found it too difficult to rhyme with. Some lyrics sites suggest, instead of “this abandon,” the neologism “disabandon,” which wouldn’t make sense even if it was a recognized word.

In Billie Holiday’s 1940 and 1945 versions, she sings a combination of the two lyric versions. It’s the original lyric modified by superimposing parts of the second. The first line of her chorus is borrowed from the second lyric, and she incorporates modified versions of the final two sections of this “Ruth Etting version” lyric. Holiday sings the same words in each of these two versions, but the 1940 recording has the chorus split into two parts connected by an instrumental bridge featuring a muted trumpet part.

In his 1947 recording, Frank Sinatra sings the original (Holman) chorus with just a single phrase modified: “My life a hell” becomes “My life’s a wreck.” But when he repeats the last section, he drops the “‘s” from “life,” and makes another minor change.

Although by today’s standards the original lyric is mild as milk, the use of the word “body,” in the implied sense of something offered freely for another’s service, use, or enjoyment, was apparently considered inappropriate for song lyrics in 1930, especially when the reference was to a woman’s body.

LikeLike

Apr 22, 2012 @ 11:55:53

Well I need to “abandon” this thread for the time being, in about 2 hours I need to give a visiting lecture at Amherst College on….. Body and Soul! Look forward to whatever modifications you make.

LikeLike

Feb 22, 2015 @ 03:43:23

Do listen to Morgana King’s rendition ot the verse, discussed in the forgoing.

I think she pulls it off.

LikeLike

Feb 22, 2015 @ 21:10:19

Derek, Hi. Spurred on by your exhortation, I’ve been listening to two versions by Morgana King today, one from the 1958 album Morgana King Sings the Blues, and the other evidently first released on the 1986 LP Simply Eloquent, and later found on the 2000 compilation Tender Moments. I much prefer the latter, which goes something like this

LikeLike

Feb 26, 2015 @ 04:45:38

Hi Doc. Thank you for introducing me to this version, I must agree that it is better, her voice has ripened as one would expect over some 28 years. She still sticks with the verse, bless her. Further she tends not to ‘over do’ her some what baroque lyric style she’s developed over the years. Example, I would cite is her rendition of ‘Gone With The Wind.

Which I quite like, but is a bit over the top.

Yours Derek

P.S. Who performed the very nice piano accompaniment?

LikeLike

Feb 26, 2015 @ 12:39:39

Hi Derek,

Agree regarding the voice, but I also prefer the Bill Mays arrangement for this version, the accompaniment with piano only, by Mays. In a product description, CD Universe lists the following personnel: Morgana King (vocals), Bill Mays (keyboards, vocals), Ted Nash (flute, clarinet, saxophones), Steve La Sina (bass), Adam Nussbaum (drums). I’m guessing the February 24, 1965 recording date diving by CD Universe is an error, as they also give the same calendar day in 1986 as the recording date. Dusty Groove credits the same personnel in an album promo.

LikeLike

Dec 02, 2015 @ 19:05:53

Hi Doc. I just came across this fascinating site while researching who wrote the alternate lyrics. Thanks for doing all that research! I do, however, have to respectfully disagree with your assessment of their worth. I adore the alternate lyrics, and I literally cringe at certain sections of the original lyrics. IMO, the original lyrics read like a tale of obsessive stalker love, which is something I personally find hard to identify with (thank goodness). I feel that the story the alternate lyrics tell is a far more universal. To me, it sounds much more like the thought process of someone who is stumbling their way through the shock of having their heart smashed to pieces by a partner who has been lying to them. I also I find the imagery and near rhymes in the alternate lyrics to be richer (“I was a mere sensation/My house of cards had no foundation” is a passage I like a lot). The rhyme that you seem particularly bothered by in the verse (“abandon,”) I’ve interpreted as “And I am left in this: abandonED, so far removed from all that I have planned on” (emphasis added for clarity). It’s still a forced rhyme, I’ll grant you, but it makes about as much sense as “Are you pretending?/It looks like the ending/unless I can have one more chance to prove, dear” (pretending what? prove what?). Anyway, that’s my two cents. Thanks for sparking the discussion! It’s always nice to find other people who care about these details as much as I do.

LikeLike

Dec 09, 2015 @ 12:46:21

Hi Mary,

Thanks for the taking the time to leave a kind compliment and for rekindling the conversation on the various “Body and Soul” lyrics. You might be onto something with “And I am left in this, abandoned.” That phrase makes sense. I’ve just listened again to the 1930 recordings by Helen Morgan, Ruth Etting, and Annette Hanshaw, and while I couldn’t positively identify the past tense on the final word of the phrase in any of those instances, it’s a possibility in each case. The “-ed” ending would naturally be muted when sung at the end of a line.

I’m with you regarding “obsessive stalker love” lyrics. But such lyrics are, unfortunately, ubiquitous in American popular song, past and present. The first example I thought of was “Every Breath You Take” (Sting) by the Police, which reads like the stalker creed:

How many other popular songs of unrequited or lost love contain one or more of the following expressions in some form?

Such lyrics are often disturbing to me, and I believe they generally betray unhealthy viewpoints and states of mind. They often contain veiled or outright threats that someone may be in danger of being harmed if someone doesn’t get their way. I typically omit such songs, if forewarned, from my own listening experiences, or if I do listen to them it may be because I am appreciating other elements of the song and can laugh at the absurdity or foolishness of some of the words. However, I have compromised in including many songs with such lyrics in this website. I’m concerned about this. Have not infrequently considered dashing the whole site for fear of promulgating songs which may nurture and deepen hopelessness, dependence, and feelings of despair.

Regards, doc (-̮̮̃-̃)

LikeLike

Dec 09, 2015 @ 13:02:16

Mary,

I agree that these lines are not particularly strong, and the lyric I previously championed as “greatly superior” to the other isn’t all that wonderful. I may do, or perhaps together you and I may do a more extensive comparative analysis of the different “Body and Soul” lyrics in the future. For now, I will say that “pretending” might mean “pretending to leave,” something that one might do to see what kind of effect it would have. Or it could mean pretending to care, or not to care, according to one’s whim. And “chance to prove,” in the context in which it is used, might mean something like “chance to prove how much I love you/care about you/am the best dang thing you’ll every find, etc.”

LikeLike