Aida Overton Walker slide show, gallery, and links

___________________________________________

page originally published on 29 June 2012: latest edit: 29 November 2021

(below) Excerpts from A History of African American Theatre by Errol G. Hill, James Vernon Hatch (2003), in Chapter 5, “New vistas: plays, spectacles, musicals, and operas,” by Errol G. Hill, p. 166:

Aida Overton Walker theatrical photos by White Studio, NY, c. 1900-1912*

c. 1900-1904, White Studio

- W1 (possibly by White Studio)

- W2a

- W2b

- W3a

- W3b

- W4

- W5

- W6

- W7

1907, White Studio

- W8a

- W8b

- W8c

- W8d

c. 1908-1912, White Studio

- W9a

- W9b

- W10a

- W10b

- W10c

_____________________

as Rosetta Lightfoot in In Dahomey, by Cavendish Morton, 1903, (CM 1-3 © National Portrait Gallery, London)

- CM 1

- CM 2

- CM 3

- from CM 1 (trading card)

- trading card

- possibly by Cavendish Morton

Abyssinia, 1906

Aida Overton Walker — all images, c. 1892-1912, including sheet music covers

- W1 (possibly by White Studio)

- George Walker, Bert Williams, and Aida Overton Walker, date unknown

- CM 1

- from CM 1 (trading card)

- CM 2

- CM 3

- trading card

- possibly by Cavendish Morton

- In Dahomey, c. 1902-1903

- George Walker, Aida Overton Walker, and Bert Williams, In Dahomey, c. 1902-1903

- W2a

- W2b

- W3a

- W3b

- W4

- W5

- W6

- W7

- W8a

- W8b

- W8c

- W8d

- W9a

- W9b

- W10c

- W10a

- W10b

- from Porto Rico (Ford Dabney) sheet cover, 1910

- ad in The New York Age, 31 August 1911

- Sons of Ham, 1900-1901

- In Dahomey, 1902

- 1904

- 1904

- Bandanna Land, 1908

- Bandanna Land, 1908

- Bandanna Land, 1908

- 1909

- Porto Rico (rag intermezzo) by Ford Dabney, 1910

- from revue His Honor, the Barber, 1909-1911, which debuted off-Broadway in 1909; 15 performances on B’way, May 1911

- 1911

_________________________________________

Aida Overton Walker biography and article:

- Wikipedia

- WikiVisually

- Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History by Constance Valis Hill (2009), pp. 36ff

- “The Later Years of Aida Overton Walker; 1911-1914“ by Wells Thorne, archived from the defunct (as of December 2018) blackacts.commons.yale.edu

- “The Brightest Star”: Aida Overton Walker in the Age of Ragtime and Cakewalk by Richard Newman, published in Prospects, Vol. 18, October 1993, pp. 465-481 (abstract at zotero.org)

- book

- Moving Performances: Divas, Iconicity, and Remembering the Modern Stage by Jeanne Scheper (2016), Chapter 1: “The Color Line is Always Moving: Aida Overton Walker,” pp. 22-60

- “Black Salome: Exoticism, Dance and Racial Myths” by David Krasner, which appears as chapter 10 (in part III) of the book African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader, edited by Harry J. Elam, Jr., David Krasner (2001), pp. 192ff.

Williams and Walker Company:

- Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America’s First Black Star by Camille F. Forbes (2008)

- Chapter 2: The Williams and Walker Years, pp. 37-163

On In Dahomey: Williams and Walker Company pioneers new territory for African-American theater; Aida Overton Walker elevates the cakewalk and teaches her interpretation of the dance to society in New York and Great Britain

- The Guide to Musical Theatre — synopsis of In Dahomey and Dahomey (earlier version)

- In Dahomey: A Negro Musical Comedy — music by Will Marion Cook, lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar, book by Jesse A. Shipp; edition published in London by Keith, Prowse & Company Ltd., c. 1903 — The Google eBooks preview evidently includes the whole score, including lyrics, of the musical as “[p]roduced at the Shaftesbury Theatre May 16th 1903.” The script is not included (see the next link).

- I only checked each page carefully to about halfway through and noticed no pages missing, though there are two extra copies each of pages 12 and 13, one of the page 13 copies partially obscured by a ruler, and one duplicate each of pages 60 and 61.

- The Music and Scripts of ‘In Dahomey’ — Will Marion Cook, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Jesse Shipp, edited by Thomas L. Riis (1996) — Google eBooks preview: Presently available in the preview are 1. An introductory chapter by the editor titled “In Dahomey in Text and Performance” (33 pages) and 2. the first two acts (of three) of one of the extant versions of the script, by Jesse Shipp.

- Rewriting the Body: Aida Overton Walker and the Social Formation of Cakewalking by David Krasner, published in Theatre Survey, Volume 37, Issue 02, November 1996, pp. 67-92 (abstract, Cambridge Journals Online)

- Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America’s First Black Star by Camille F. Forbes (2008)

- Chapter 2: The Williams and Walker Years, p. 100ff. (link added, 27 April 2017)

- Bodies in Dissent by Daphne Brooks (2006), Chapter 4: Alien/Nation — Re-Imagining the Black Body (Politic) in Williams and Walker’s “In Dahomey”, pp. 207ff.

- The Real Thing, essay by David Krasner, pp. 99-123 of the book Beyond Blackface: African Americans and the Creation of American Popular Culture, 1890-1930, edited by W. Fitzhugh Brundage (2011)

- “In Dahomey” portraits photographed by Cavendish Morton, 1903 @ digital collections of the National Portrait Gallery, London (https://www.npg.org.uk)

_____________________

(above) The Paradise Roof Garden of Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre, from the article “New York’s Incredible Lost Rooftop Theatres,” by Messy Nessy, 17 March 2017 — This is where Aida Overton Walker performed her Salome dance in 1912.

Excerpt from the book Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America by Karen Sotiropoulos, pub. 2006, pp. 176-177 (Page 176 is missing from the Google eBooks preview.):

Although Walker won praise for her classic performance of “Salome” as part of a black musical comedy, when she performed the same dance as a solo dancer at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater in 1912, she was ridiculed. “Salomania” had, in effect, “domesticated” Salome, earning the “Dance of the Seven Veils” designation as a classical dance and opening the doors of Oscar Hammerstein’s opera house to a revival of the Strauss opera in the spring of 1909. Hammerstein and his son, Willie, had seen Walker perform the dance in Bandana Land [sic], and invited her to perform this newly ordained classical dance at their theater. Although white critics had praised Walker’s performance on the all-black stage, most of them rejected her inclusion as part of a “higher class” attraction. One critic announced that “a Salome of color” was “a direct smash in the face of convention.” Of Walker’s 1912 performance at Hammerstein’s, another critic wrote, “Ada Overton Walker’s single-handed ‘Salome’ was funny,” and that the music was “all wrong.” Instead of the “heavy classic stuff … the bunch should have been playing Robert E. Lee.”34 These white critics missed the irony that the dance had earned more legitimate status because of the vaudeville-induced “Salomania,” and arguably, because of Walker’s magnificent performance in Bandana Land.

Although Walker won praise for her classic performance of “Salome” as part of a black musical comedy, when she performed the same dance as a solo dancer at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater in 1912, she was ridiculed. “Salomania” had, in effect, “domesticated” Salome, earning the “Dance of the Seven Veils” designation as a classical dance and opening the doors of Oscar Hammerstein’s opera house to a revival of the Strauss opera in the spring of 1909. Hammerstein and his son, Willie, had seen Walker perform the dance in Bandana Land [sic], and invited her to perform this newly ordained classical dance at their theater. Although white critics had praised Walker’s performance on the all-black stage, most of them rejected her inclusion as part of a “higher class” attraction. One critic announced that “a Salome of color” was “a direct smash in the face of convention.” Of Walker’s 1912 performance at Hammerstein’s, another critic wrote, “Ada Overton Walker’s single-handed ‘Salome’ was funny,” and that the music was “all wrong.” Instead of the “heavy classic stuff … the bunch should have been playing Robert E. Lee.”34 These white critics missed the irony that the dance had earned more legitimate status because of the vaudeville-induced “Salomania,” and arguably, because of Walker’s magnificent performance in Bandana Land.

Ever conscious of the gaze of whites, Aida Walker, and the Williams and Walker Company, had carefully orchestrated her performance in Bandana Land so that it would not upset white patrons. Bert Williams followed her performance with a burlesque of the dance, one incorporating enough racial stereotype to distract white audiences from Walker’s serious performance.

From the book Moving Performances: Divas, Iconicity, and Remembering the Modern Stage by Jeanne Scheper (2016), Chapter 1: “The Color Line is Always Moving: Aida Overton Walker,” p. 55:

When Aida Overton Walker chose to perform the Salome dance as a serious piece of choreography on its own, removed from a revue context of blackface vaudeville productions like Bandanna Land, she was featured at the famous Hammerstein’s Roof Garden theater in New York in 1912. William Hammerstein [manager of the theater for the owner, his father the theater impresario Oscar Hammerstein] did not miss the opportunity to use the racial identity of the dance as the key ingredient for a publicity stunt. We learn from a clipping, with its not so subtle word play, “Salome was a Dark Secret,” that Hammerstein kept the identity of the new dance undisclosed as a stunt to draw attention to his venue. “The identity of the Salome Dance so carefully concealed for many weeks turns out to have been a dark secret which William Hammerstein decided yesterday he had kept long enough,” the review reads.

____________________

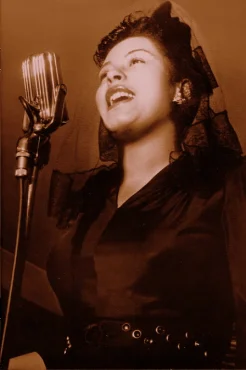

Aida Overton Walker’s male impersonation for the number “That’s Why They Call Me Shine” in the revue His Honor, the Barber (1909-1911) inspired a tribute by Florence Mills in 1924 (image, above right). From the book Florence Mills: Harlem Jazz Queen by Bill Egan (2004), p. 110:

Florence’s third scene [in Dixie to Broadway, 1924] introduced one of her most successful songs, “Mandy, Make Up Your Mind.” To the audience’s surprise she appeared in male formal dress as the groom, with chorus girl Alma Smith the tardy bride. All the company got into the act, either as bridesmaids, maids of honor or groomsmen. Florence’s male attire was her tribute to Aida Overton Walker‘s famous “That’s Why They Call Me Shine” routine.

Multiple instrumental versions of the song “That’s Why They Call Me Shine” were released in 1924, under the title “Shine.” SecondHandSongs.com indicates that an 18 April 1924 recording by The California Ramblers was the first recording of the song under that title. “Shine” eventually became both a pop and jazz standard, with some recordings featuring a new lyric by Lew Brown that was first incorporated, according to SecondHandSongs.com, on a 1929 recording.

On the “Friends and Associates” page of Bill Egan’s website FlorenceMills.com, the author suggests that Florence Mills had paid tribute to Walker much earlier in her career, at age 7:

Florence’s first professional engagement came in 1903 when, as “Baby Florence,” she featured in a guest spot singing Aida Overton Walker’s specialty number “Miss Hannah from Savannah” in the Avery and Hart production of the Williams and Walker show The Sons of Ham [sic].

Egan also indicates, on the “Friends and Associates” page, that Florence’s sister Olivia Mills (later Wiltshire) had been known to impersonate Aida Overton Walker, before her retirement in 1915 to raise a family. This claim is partly corroborated in a paragraph on Egan, page 17, which quotes from a 1914 annual stage review in The Freeman (an African-American newspaper of Indianapolis, Indiana, published from 1884-1927): “Olivia succeeds nicely in her male impersonation.” Such impersonations, suggests Egan, “followed the tradition of Aida Overton Walker in her That’s Why They Call Me Shine routine.”

_____________________________

On several gallery additions, 2013-2017:

(below, top row) The image on the left was added to my Aida Overton Walker slide show and gallery in October 2013. It appears to be a displayed clipping from the front page of the August 10, 1929 issue of the newspaper The Chicago Whip. I dated this image and the second of the three images after discovering that AOW evidently wears in each of them the same necklaces, earrings, and hair accessory — perhaps a comb or a band of some kind — as is worn in the third, which I’ve cropped from an image that appears on covers of sheet music, dated 1906, for the song “Build a Nest for Birdie” (see below). The same garments (loose-fitting blouse and dress or skirt) are worn in the second and third of the three images. The inscription on the third, partially lost in cropping, appears to have originally included the notation “Abyssinia — 06.” Note that AOW’s married surname “Walker” has also evidently been cropped off the third image. The second image was added to the page c. 2012-13. The third image was added on 11 September 2017, after I cropped it from the “Build a Nest for Birdie” sheet music cover, which had been added to the page in February 2014.

(above, bottom row) These two edits of images from a photograph, c. 1906, of Aida Overton Walker in costume for Abyssinia, were added to the page on 13 February 2016.* In the photo, Aida wears the same costume worn in the second and third images in the top row immediately above, including blouse, necklaces, earrings, and hair accessory.

The same hair accessory worn in the group of five images immediately above, seems to be worn by Walker in the image used on the cover of the sheet music for the song “I’ll Keep a Warm Spot In My Heart for You” below left, from the 1906 show Abyssinia, and in the photo of a scene from the show below right. The “Warm Spot” sheet music cover was added to the AOW gallery in March 2013; the scene from Abyssinia photo has been in the gallery since October 2012, though it was replaced with an image of better quality on 16 December 2015.

(above left) images of George Walker and Aida Overton Walker in costume for the 1906 Williams & Walker show Abyssinia, on the cover of sheet music for the song “I’ll Keep a Warm Spot In My Heart for You”

(above right, l. to r.) unknown, Aida Overton Walker, and (in blackface) Bert Williams in a scene from Abyssinia

I’ve found no evidence that Aida Overton Walker ever performed the song “Build a Nest For Birdie,” though ordinarily the use of her image on a sheet music cover would indicate that she performed the title song in a show. In this instance, however, it appears that her image may have been used on the cover to hint at the presence of advertisements for sheet music for songs from Williams & Walker shows within the pages that follow. Two cases illustrate:

I’ve found no evidence that Aida Overton Walker ever performed the song “Build a Nest For Birdie,” though ordinarily the use of her image on a sheet music cover would indicate that she performed the title song in a show. In this instance, however, it appears that her image may have been used on the cover to hint at the presence of advertisements for sheet music for songs from Williams & Walker shows within the pages that follow. Two cases illustrate:

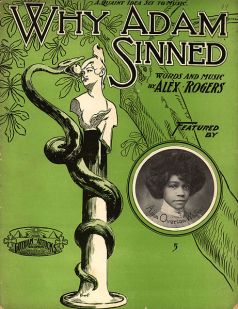

1. The sheet cover at left is from an edition of early sheet music for “Build a Nest For Birdie” that is available in the digital collections of the Performing Arts Encyclopedia at the Library of Congress website. The back page of this edition contains the notice “NOW READY: Our Williams & Walker Dance Folio, Containing All Their Recent Successes.” The page also contains small copies of the first pages of the sheet music for four songs. Among the four is “Why Adam Sinned,” which had been featured by Aida Overton Walker (AOW) in the Williams & Walker show In Dahomey, which opened on Broadway in February 1903.

2. Another early edition (dated c. 1906) of “Build a Nest For Birdie” sheet music, available at the Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music of the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections, featuring the same cover, has a few bars of the Bert Williams song “Let It Alone” on page 2, followed by the music for the title song on pages 3 to 5. The back, page 6, has advertisements for “Six Song Successes from Williams & Walker’s New Musical Creation Abyssinia,” providing the titles and three to four bars of notation for each. The songs included, each with music by Bert Williams, are: “Here It Comes Again,” “The Tale of the Monkey Maid (or, Die Trying),” “Rastus Johnson, U.S.A.,” “Where My Forefathers Died,” “It’s Hard to Find a King Like Me,” and “The Jolly Jungle Boys.” According to IBDb, “Let It Alone” was not among the songs included in the score of Abyssinia on opening night. However, various sources describe it as a song from the show, suggesting that it was added later. See, for example, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919, by Tim Brooks (2004) 2010 edition, p. 118.

Note also that directly above AOW’s photo on the cover of the “Build a Nest For Birdie” (m. James T. Brymn, w. R. C. McPherson) sheet music is a reference to a previous song by the same songwriting team, “Josephine, My Jo,” which had been a late addition to an earlier Williams & Walker show, Sons of Ham (1900-1902), though evidently not sung by Aida.

(above, left) Image from an undated, signed photograph of AOW by White Studio of N.Y., added to my AOW gallery on 9 February 2014, replaced by a different edit, this one, on 13 February 2014. Aida’s married surname “Walker” in the signature is difficult to read against the dark background and partially truncated. Aida wears the same dress and necklace as in the photo above right, which had been published at my AOW slide show and gallery page in June 2012. The hairstyle also appears to be virtually identical, though the hair is topped with an elaborately decorated headdress or hat in the left image. Both images are by White Studio of New York.

On 9 February 2017 I noticed that the headdress or hat worn in the center photo (added to the page in March 2013), also by White Studio of N.Y., appears to be the same one worn in the photo at the left. Also, the hairstyle in the center photo seems very similar to that in the other two. I’m still working on dating these. See also the similar hairstyle in the portrait by White Studio of N.Y (below left), which was used on the 1904 sheet music for the song “Why Adam Sinned,” from In Dahomey (below right).

(below) Sheet music for two songs from the 1908 Williams & Walker show Bandanna Land (added to the site on 9 and 12 February 2014, respectively) each containing a photographic image of AOW, and crediting her for performing the song in the show. The cover of “I’m Just Crazy ‘Bout You” indicates that it is “The Hit of Bandana Land” [sic]  and that it had been “sung with great success by Aida Overton Walker.” The cover of “It’s Hard to Love Somebody (Who’s Loving Somebody Else)” notes that it was “introduced by Aida Overton Walker in Williams and Walkers [sic] latest success Bandanna Land.”

and that it had been “sung with great success by Aida Overton Walker.” The cover of “It’s Hard to Love Somebody (Who’s Loving Somebody Else)” notes that it was “introduced by Aida Overton Walker in Williams and Walkers [sic] latest success Bandanna Land.”

The image of AOW used on the cover of the sheet music for “It’s Hard to Love Somebody” shows her in costume as Rosetta Lightfoot for the show In Dahomey. The image is evidently derived from the photograph at right, which I added to the AOW gallery in March 2013. The photo was probably taken in the period 1903-1904, during which the runs of several productions of In Dahomey occurred.

_____________________________

See also the following related Songbook pages on Bert Williams and George Walker, during the Walker & Williams years, 1896-1909:

See also the following related Songbook pages on Bert Williams and George Walker, during the Walker & Williams years, 1896-1909:

- Bert Williams & George Walker: selections from their first Victor recording session, 11 October 1901

- Bert Williams and George Walker: selected sheet music slide show and gallery, 1896-1908

- Bert Williams and George Walker slide show and gallery, 1896-1909

_____________________________

* Identifying and dating the White Studio, NY, images, including arguments for the most likely year of creation:

Note: In January 2021 I found other copies of images W3a,b, W4, W6, and W7 in a collection that includes numerous undated photos of members of Williams & Walker Company in costumes that may have been worn in Sons of Ham. There were two Broadway productions of Sons of Ham, the original production which opened on 15 October 1900 and a revival which opened on 29 April 1901. Each run lasted just eight performances. The same collection contains other photos of Aida in the costumes seen in images W3a,b, W4, and W7. If my conclusion (at the bottom of this footnote) that images W1-W7 might have all been created at or about the same time is correct, then it follows that if one of the images was created during the years 1900-1901, then they all might have been created during that period.

- W1

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1902 — The image was used on the cover of the sheet music for “I’d like to be a Real Lady.” The song was copyrighted in 1902, and according to the Library of Congress, the sheet music featuring image W1 was created and published in 1902.

- W2a,b — Image 2b was added to my main Aida Overton Walker page in 2016. Image W2a is a new edit of that image created on 3 March 2019.

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1902 – The hairstyle or wig resembles that worn in image W1, which was used on the cover of the sheet music for “I’d like to be a Real Lady,” published in 1902.

- 1904 — The image was used on the cover of the sheet music for “Why Adam Sinned,” published in 1904.

- W3a, b — White Studio #84 — I recently found the image that I’ve labeled W3a at the Beinecke Digital Collections of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Image W3b (source unknown) is a smaller copy of the same photograph, which I’ve had on this page since June 2012.

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1902 – The hairstyle or wig resembles that worn in image W1, which was created no later than 1902.

- 1904 — The hairstyle or wig resembles that on the 1904 “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music cover.

- W4

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1902 – The hairstyle or wig resembles that worn in image W1, which was created no later than 1902.

- 1904 — The dress, pearl necklace, hairstyle/wig, and earrings worn by Aida each appear to be the same worn in images W3a and W3b. The hairstyle seems to be the same as that in the photo used on the 1904 “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music cover. The hat/headdress appears to be the same as that worn in images W5 and W6.

- W5 — White Studio #63 – source unknown; added to this page in March 2013

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1901 — The luxurious, ruffle adorned, white dress worn in images W5 and W6 somewhat resembles the dress worn in the illustration on the cover of the sheet music for “Miss Hannah from Savannah,” published in 1901.

- 1902 – The hairstyle or wig resembles that worn in image W1, which was created no later than 1902.

- 1904 — The hairstyle seems to be the same as that in the photo used on the 1904 “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music cover. Also, the elaborately decorated hat or headdress seems to be the same one worn in image W4, which is one of the three “pearl necklace” photos (images W3a, W3b, W4, and W7), all of which I’ve tentatively dated 1904 because the hairstyle in each seems to the same as that in the photo used on the 1904 “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music cover.

- W6 — White Studio #64 — I recently found this image, which I’ve labeled W6, at the Beinecke Digital Collections of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- 1901-1904 — See Note, above, and image W5.

- W7 — This image is an edit by me of an image found in the Flickr photo stream of Bluesy Daye on about 1 March 2019.

- 1900-1901 — See Note, above.

- 1902 — The hat looks like it might be the same one worn in image W1, which was created no later than 1902, and the hairstyle/wig also resembles that worn in image W1.

- 1904 — The hairstyle or wig appears to be the same as that in images W2-W6, which may have been created in 1904.

- W8a,b,c,d — Images W8a,b, and d are my own edits of images recently found in Yale University’s Beinecke Digital Collections.

- 1907 – One of the two inscribed photos in the cardboard photo holders is dated 1907, the other 1908. I’m guessing that the photo was taken around 1907. It certainly was no later than that year.

- W8a – inscribed “To Mr. & Mrs. [Nora] Holt with love, Aida Overton Walker 1907.”

- W8b – inscribed “Yours from Bandana Land Aida Overton Walker 1908.”

- W8c – uninscribed edit from unknown source, posted on my main AOW page years ago

- W8d – evidently cropped from the image used for W8a

- 1907 – One of the two inscribed photos in the cardboard photo holders is dated 1907, the other 1908. I’m guessing that the photo was taken around 1907. It certainly was no later than that year.

- W9a,b — Image 9a was recently found in the NYPL Digital Collections, where it is dated 1911. Image 9b is an edit by me of that image, made by simply removing the brown tint.

- 1908 — In the article “Black Salome: Exoticism, Dance and Racial Myths,” by David Krasner, which appears as chapter 10 (in part III) of the book African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader, edited by Harry J. Elam, Jr., David Krasner (2001), pp. 192ff., on pp. 203-205, the author claims that what I’ve labeled image W9 shows Overton Walker in the costume that she wore in the Salome dance that she performed with Bert Williams in the 1908 musical revue Bandanna Land, and that for her more modern interpretation of the dance in 1912, she wore a loose-fitting gown, similar to those commonly worn by Isadora Duncan. If Krasner is correct in dating image W9 1908, then image W10 is also from 1908.

- The biography of Ada [sic] Overton Walker in the online Performing Arts Encyclopedia of the Library of Congress says:

- This explains why IBDb does not list that number among the opening night songs of Bandanna Land, which had a run of 89 performances on Broadway at the Majestic Theatre from 2/03/1908 to 4/18/1908.

- The book Incidental and Dance Music in the American Theatre from 1786 to 1923 Volume 1 by John Franceschina (2017?), on p. 1907, says that the music for the Bandanna Land number “The Dancing of Salome” was composed and arranged by Joe Jordan.

- The Wikipedia page on Joe Jordan says: “In New York, Jordan wrote a couple of songs for Ada Overton Walker, first “Salome’s Dance” and then in 1909 “That Teasin’ Rag”.”

- 1911 — The date 1911 attached to image 9a at the New York Public Library Digital Collections may be incorrect.

- 1912 — Overton Walker performed her latest interpretation of the dance of Salome at the Paradise Roof Garden of Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre in a production that opened in August 1912.

- W10a,b,c — I’ve had these images, source unknown, in my main AOW page since 2012, though a couple of them were updated in 2017.

- 1908 — See the explanation regarding this date for image W9.

- 1910 — The date 1910 attached to the image at NYPL Digital Collections may be incorrect.

- 1912 — Overton Walker performed her latest interpretation of the dance of Salome at the Paradise Roof Garden of Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre in a production that opened in August 1912.

Factors which, in combination, suggest that W1-W7 may have each been created in or before 1902, and likely during the period 1900-1901:

- See Note, above, near the top of this footnote, which suggests that images W3a,b, W4, W6, and W7 may have been created during the years 1900-1901.

- The same hairstyle or wig seems to be worn in each of the images.

- Image W1 was used on the cover of the sheet music for “I’d like to be a Real Lady.” The song was copyrighted in 1902, and, according to the Library of Congress, the sheet music featuring image W1 was created and published in 1902.

- In images W3(a,b), W4, and W7, Aida appears to be wearing the same set of pearls.

- The hat worn in W1 appears to be the same one worn in W7.

If the hat is the same in W1 and W7, and the pearls are the same in W3(a,b) W4, and W7, then W1,3,4, and 7 were likely shot at or around the same time. Further, since the same hat or headdress is worn in W4, W5, and W6, and given that W1 was created in or before 1902, it follows that W1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 may have all been created on or around the same date, in 1902 or earlier. The chronological connection of W2(a,b) to the others in this group of images is suggested in part by the presence of a hairstyle or wig that closely resembles that found in each of the others. Also, W2 was created no later than 1904, when it was used on the cover of the sheet music for “Why Adam Sinned.”

Aug 03, 2012 @ 04:48:18

Appreciate you sharing, great blog. Much thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aug 03, 2012 @ 14:32:13

Hi, Taniya

Pleased to meet you. Thanks for stopping by.

LikeLike

Jan 13, 2013 @ 00:13:25

Hey, Just wanted to say thanks so much for this great page! It has the most images I on the web. I came here looking for lyrics to Aida’s song/poem called “why Adam sinned” the net has basically nothing at all. If you know of any more links or info I would love to know about it. Either way, thanks again for the blog!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 13, 2013 @ 13:00:08

Hi Monique,

The lyrics can be found in the sheet music. Why Adam Sinned was written by songwriter Alex Rogers (1876-1930) and published in 1904.

Online copies of the sheet music (revised 17 July 2018):

1. “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music page of the African American Sheet Music collection of the Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship (old catalog system)

2. “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music page of the African American Sheet Music collection of the Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship (new catalog system)

3. “Why Adam Sinned” sheet music page of the E. Azalia Hackley Collection, Digital Collections of the Detroit Public Library

LikeLike

Mar 06, 2013 @ 04:07:22

You continue to amaze me Doc ! : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 06, 2013 @ 16:48:18

Wotcha Don, Thanks

LikeLike

Dec 26, 2013 @ 21:50:19

Music Covers knocked me out. Great job on the lady. Your research and website postings a joy. Thanks as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dec 27, 2013 @ 01:24:26

Thanks, Anon

Some interesting covers, I agree. Some of the photographs of AOW make it difficult to believe, when you consider the typically stiff, formal look so common in photographs of people from this era, that she even belongs to it.

LikeLike

May 04, 2014 @ 01:32:21

Are there any recording of Aida still in existance or films of her dancing?

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 04, 2014 @ 14:45:12

D’Lynn,

I don’t think Aida made any audio recordings. Haven’t heard of any. And I’m not aware of any film footage of her dancing either. I’ll let you know if I do find anything. — doc

LikeLike

Feb 03, 2016 @ 13:48:25

This is Fabulous. Thank you for providing so many resources on a star who, unfortunately, has not been duly recognized yet paved the road for so many of us in the performing arts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feb 06, 2016 @ 00:04:23

Hi luanadancer,

Thank you for the kind comments. The absence, as far as I’m aware, of audio recordings or film footage of Aida is unfortunate, but I believe she will eventually be well-known, esteemed, and duly honored. Her time is coming.

Regards, doc

LikeLike

Jan 24, 2017 @ 12:47:56

I am writing what I believe to be the first biography of Aida’s husband George and in doing my research, no recordings or film of her have come to the surface. In fact, there are only 8 recordings of George that I know of, but I own several copies of their sheet music along with a few photographs and several postcards made between 1896 and 1903. In doing this research, I have come to understand the amazing effort that Aida brought to bear when George took ill and eventually died. When he was gone and could no longer protect himself, Aida took up for him and suffered greatly, mostly at the hands of Bert Williams’ manager who was trying to make a case for him to have honorary Whiteness and therefore, be allowed in the Ziegfeld Follies as a fly in the ointment. As a result, the feud between she and Bert was so great that he was not welcome at her funeral! I hoped that she was a part of Bert Williams’ recently discovered comedy Lime Club Kiln Field Day (1913), but that wasn’t the case. She was remarkable and like George, she deserves better!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 25, 2017 @ 20:30:20

Daniel,

Hi. Delighted to hear of your project, which is certainly a noble venture. Pease let me know if I can be of any assistance. Four or five years ago, while I was preparing my four pages on Bert Williams, George Walker, and Aida Overton Walker — see the top section of my index African-American musical theater, 1896-1926: feature pages and galleries — I planned to do a couple of additional pages, including one on George Walker. It was clear during the preliminary note taking process that the job would involve some meticulous digging and foraging. The other planned page was to have been on the American Tobacco Company advertisements which Williams, Geo. Walker, Stella Wiley, and (reportedly*) Aida Walker posed for c. late 1896. Anyway, for whatever reasons I never got so far as an outline for the page on George, and eventually put these plans on hold indefinitely as I moved on to other projects.

I have read that Aida stepped into George’s role in Bandanna Land after he became too ill to continue performing in early 1909, but I wasn’t aware of the difficult relationship wrt Bert Williams’ manager, or the feud between Aida and Bert that you refer to.

Regards,

doc

*reportedly — Neither of the females in the color lithographs (17 x 17 inches) and postcards derived from the c. 1896 American Tobacco Co. photo shoot resemble Aida, in my estimation — although this might be explained by the fact that the postcards were evidently created by painting over or colorizing black and white photographs, while the color lithographs seem to have been created as illustrations closely based on photographs — and I remain unconvinced that she was one of the two women who posed with W&W for those photographs.

LikeLike

Jan 26, 2017 @ 07:38:56

George mentions that it is her in a few editorials that he wrote that feature the Williams and Walker origin story. I have all eight images from the postcard series plus a ninth that was previously unknown to me. I also discovered why Aida spelled her name with an “I” after 1903 among other things like George’s date of birth, their actual date of marriage and the house they shared with Aida’s family in Harlem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 26, 2017 @ 16:06:04

“George mentions that it is her in a few editorials…”

That’s the sort of evidence I’ve been lacking until now. Thanks. Your first message here has inspired me to delve into the chronicles again. Books I’ve been reading that seem to have quite a bit on George, with some insights into his character, include:

Have you ever seen the original photographs that the lithographs and the postcards were created from? I’m only aware of a single photograph of Bert and George in those costumes (right; linked to full size image).

On page 44 of Spreadin’ Rhythm Around, Jasen and Jones suggest that the 17 x 17 inch color lithographs were created before the postcards, and that the postcards were at least the third series of advertising items issued that were created from the photographs taken by the American Tobacco Company, saying:

The routine [Williams and Walker cakewalk] was so funny that in 1896 the American Tobacco Company asked to photograph them in dance poses for a series of eight trading cards to advertise their Old Virginia Cheroots cigars. For the photo session, Williams and Walker were paired with two actresses from the Black Patti Troubadours company, Stella Wiley (who was Bob Cole’s wife) and Ada Overton (who would soon mary George Walker). The pictures were so popular that the company re-issued them as lithographs and, later, on postcards.

I’ve yet to find a trace of the “trading cards” that, according to Jasen and Jones, preceded the colored lithographs and postcards, or of the photographs from which all of the other items derive.

LikeLike

Jan 26, 2017 @ 16:25:01

Forbes’ version of the story, in Burnt Cork, differs from that of Jasen and Jones in that Forbes indicates that Williams and Walker handpicked Stella Wiley to pose with them for the photo session, and then she selected Ada Overton.

LikeLike

Jan 27, 2017 @ 14:24:03

Hello,

It might be a little annoying for the other viewers of the thread to have such an in depth conversation. If you like, you can call me at 206-218-4206 and I can give you more detail on what I have on this subject matter. Long story short, I have come across quite a bit of data that contradicts a lot of what has previously been written simply by following the data trail as it relates to George and Aida rather than Bert. Though very thorough, I find much of Forbes’ work to be a little biased toward the accepted narrative of the relationship between Williams and Walker.

Daniel Atkinson

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 27, 2017 @ 15:23:04

Daniel,

I was just about to suggest that we continue the conversation privately, but for other reasons, particularly that it might not be prudent to give away too much of substance regarding what might be otherwise be revealed in good time in the projected book. May I use the attached email address?

doc

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 09:07:38

A while after writing this, I recalled that George Walker wears what appears to be the same costume in the photographic image on the cover of the 1897 sheet music for “I ain’t ‘bliged to stan’ no [“n” word] foolin’,” which evidently depicts a scene in an unidentified stage show, though Bert Williams wears a different costume than that worn in the above photo, which may be from the American Tobacco Company photo shoot. See also my page Bert Williams and George Walker: selected sheet music slide show and gallery, 1896-1909.

[comment abridged, 19 April 2019]

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 07:36:01

Hello,

I can clearly understand taking the conversation “off line,” but for the record, I personally very much enjoyed listening to two scholar/researchers chat. The information about Aida is fascinating, but the dance of ideas and concepts moving between the two of you was invigorating. Be well and good hunting! Luana

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 01, 2017 @ 08:07:45

Hi Luana,

Thanks for your interest. Actually, that was pretty much the end of the conversation between Daniel and myself for now, though I hope that it will continue in the future. Congratulations on your book, What Makes That Black?, and best wishes for its success! As for myself, I’ve been delving deeply into a different musical era for the last few weeks, focusing primarily on early Motown, and will probably publish a couple of additional pages shortly.

Regards,

doc

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 08:21:15

Thank you for the best wishes on my book. I am about to submit the next one, an in-depth analysis on the aesthetic. I look forward to your pages on Motown! Love Love the sound and fascinated by the politics behind the music. Have you read “Funk, The Music, and the Rhythm of the One” by Rickey Vincent – It is about Funk music but it has a great deal of history about Motown and the transition.

Best,

Luana

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 01, 2017 @ 10:10:28

No, I haven’t seen that book yet, but I’ll look for it. Thanks. The funk I listened to when I was young (born 1958, same year as Tamla, Michael Jackson, and Prince), aside from James Brown of course, tended to be that by certain groups and artists with crossover hits in the late 60s to mid-70s, artists such as Sly & the Family Stone, Ohio Players, Rufus, etc. I watched Soul Train religiously.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 01, 2017 @ 19:36:44

I took a course from Vincent and he was outrageously informed! A deejay for many many years, and involved in the music industry for a while, he had informative and funny stories. You will enjoy the book. He also has a newer book I have not read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 01, 2017 @ 22:23:37

Luana,

Thanks for the tip on the Rickey Vincent books. May order that first one. I have an old site called funk & soul, that you’re welcome to have a look at, though I suspect that many of the videos won’t be working (needing replacement), and most of the images need re-editing due to my having had a defective monitor when those images were created. The site was built mostly from 2008-2010, and abandoned about six years ago.

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 07:44:17

I do have a question … for doc or Daniel. I had read in Monica Miller’s book “Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity” that W&W were stopped on a street in Georgia and stripped of their garments. Do you know what year?

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 09:48:19

I don’t recall hearing of that incident. Can you provide the page number in the cited book, or a link to the story?

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 09:50:05

Hello,

There are multiple versions of that story and it’s difficult to find the kernels of truth in them because they are taken from oral histories. That said, I can confirm that it did happen, but most likely not in Georgia or in NOLA as some accounts suggest. None of my research indicates that Williams and Walker were ever in Georgia. With the exception of Kentucky, they stayed out of Dixie because they strayed away from minstrel norms and (subtly by today’s standards) asserted Black sovereignty. It was an issue of safety. George Walker made two mentions of it that I know of and they both indicate that it took place in a mining camp in Colorado. The name of the town and year escape me at the moment, but I have it written down in the mishmash of notes that I’m trying to make sense of for the book. When I find it again, I’ll let you know! Either way, It was very early in their association, before they made the switch to George as the straight and Bert as the buffoon, so it had to be between mid-1894 and early 1896. Among other things, that event may have been the culminating act of cruelty that hampered Bert’s sense of social courage, something that would drive a wedge between the two partners over time and later, with Aida as well when she posthumously defended George as mentioned earlier in the thread. I hope this helps and I will secure a copy of your book!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mar 01, 2017 @ 19:57:11

Daniel, Thank you for the information and clarification. I look forward to getting the details of the town and year when you find them, I really understand about the boxes and boxes of research notes and articles! From my study I could feel that something had suppressed Bert in a big way. You may be right about the event and its impact. I assume I can credit you for the information. And, thank you for showing interest in my project. Best,

Luana

LikeLike

Mar 01, 2017 @ 23:00:03

Hi Daniel,

Thanks for the helpful information.

Regards,

doc

LikeLike

Mar 02, 2017 @ 14:32:06

Another great resource is Tom Fletcher’s 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business. He was born about the same time as George and Bert and completed his memoir about a year or two before his death in 1954. It is remarkable and an extremely rare insider’s account of life for Black performers from the days of bondage through the 1950s! It is quite expensive, but you can find ex-library copies every once in a while that are reasonable. Though I’m still looking, the only other accounts that come anywhere close to that are from the Johnson Brothers and Lester Walton who was the theatre writer for the New York Age. Unfortunately, most of them didn’t live long enough to tell the tale. Most everything else comes from Black newspapers, particularly the New York Age, Broad Axe, Colored American, Indianapolis Freeman, Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Inter-Ocean, The Rising Sun and the Afro-American. A treasure trove of context!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 02, 2017 @ 15:47:40

Daniel,

Are those newspaper resources available online, digitized, or would it be primarily microforms?

LikeLike

Mar 02, 2017 @ 17:40:57

Microfilm works, but it’s slow and you can’t query it as you can a digitized version. Sometimes, that’s all there is and I’m grateful to have it! Newspapers.com (a subscription service) has a lot, but you might have to go to state historical societies for some local information and the more obscure Black newspapers. If not, then you’ll have to go through Readex, and that requires access to an institution with deep pockets! Ancestry.com (via your local library) can give you access to census, birth, marriage and death records too and that is a major help. Also, this kind of stuff is scattered in archives and personal collections all over the country and Western world, so some luck coupled with persistence is the only thing that will win the day. Very often the information is contradictory and or fragmented, so it can be frustrating work, but when I come across a find that adds to the historical record, I’m over the moon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 02, 2017 @ 19:13:28

Thanks, Daniel.

You got that right! Precisely what I’m going through right now on early Motown history, though so far I’ve used only sources (books, articles, other websites and blogs) that are available free online.

Those diamonds in the rough…

LikeLike

Mar 02, 2017 @ 17:42:22

And I forgot http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ This one is free!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person