1890-1899 selected hits and standards

____________________________________

Originally published on 21 June 2009; latest edit: 24 October 2021

1891

1891

Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay (African-American traditional)

1892

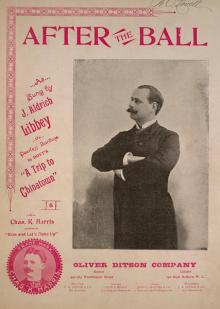

After the Ball (Charles K. Harris)

Daisy Bell (Harry Dacre)

1893

The Cat Came Back (Harry S. Miller) – separate feature

Can’t Lose Me, Charlie (Henry S. Miller) – Questions about songwriting credit considered in the text

1894

The Sidewalks of New York (Charles B. Lawlor, James W. Blake)

1895

The Band Played On (John F. Palmer, Charles B. Ward)

You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You(‘ve) Done Broke Down (Ben Harney, John Biller)

1896

A Hot Time in the Old Town (m. Theodore August Metz, w. Joe Hayden)

1899

Maple Leaf Rag (Scott Joplin )

My Wild Irish Rose (Chancellor Olcott)

_________________________

In a review titled “A Discographic Deception,” dated July 13, 1987, by expert discographer and sound historian Tim Brooks, of the notorious but influential venture into acoustic-era popular music chart fabrication by Joel Whitburn in his 1986 book Pop Memories 1890-1954: The History of American Popular Music, the author exposes flaws in Whitburn’s research methodology, and reveals numerous instances of Whitburn’s astonishingly bad habit of mispresentating sources. In case after case, according to Brooks’ analysis, Whitburn’s cited sources contain nothing like what he says they do, and specifically do not contain the periodic “lists of top popular recordings,” sales data, or ranking information he attributes to them, and which might have contributed to the chart data he claims to have derived from them. Whitburn’s source of “sheet music sales” data for acoustic-era recordings is unidentified. A response from Joel Whitburn follows the review.

Quotes from the 13 July 1987 Tim Brooks review “A Discographic Deception,” regarding Whitburn’s Pop Memories 1890-1954:

…it must be said, the entire book is a colossal fraud.

But wait, you say, you didn’t know there were any popular charts in 1890? You are right. Whitburn simply made them up.

The great danger is that Whitburn’s apparently precise data, with its impressive looking sources, will be reprinted and enshrined as historical fact by others. This has already begun to happen…Whitburn has certainly been misleading in not making it clear that his “charts” are entirely speculative, and, as we have seen, none too accurate.

In a later scathing 26 November 1989* review/exposé by Tim Brooks of Joel Whitburn’s Pop Memories the author wrote,

This is a dangerous book. … Here we have a whole book full of misleading information, presented in such a factual, almost statistical manner that it is bound to be quoted.

From the introduction of the book Popular American Recording Pioneers:1895-1925 by Tim Gracyk with Frank Hoffmann (2012), p. 11:

A few writers in recent years, following the example of Joel Whitburn’s Pop Memories: 1890-1954 (Record Research Inc., 1986), have cited precise chart numbers for early recordings — what records after being released were number one, number two, number three, and so on. It is a deplorable trend, and I never refer to chart positions. Primary sources provide no basis for assigning chart numbers. No company files tell us precise numbers; trade journals never systematically ranked records…

At no time in the acoustic era was enough information compiled or made available about sales for anyone today to create accurate charts or rank best-sellers, and the further back in time we go, the more difficulty we have in identifying hits. Even if one had access to sales figures of the 1890s, a chart of hits means little for an era when records of many popular titles were made in the hundreds, not thousands or millions…

All chart positions concerning recordings of the acoustic recording era are fictitious, and since they mislead novice collectors, they do much harm.

Billboard published the first singles popularity charts in 1940 (see the section “History, methods and description” in the Wikipedia article on Billboard charts). The Hit Parade chart first published in 1936 seems to have been something else, though the Wikipedia article on Billboard chart history contains contradictory definitions of the term hit parade. Wikipedia’s article on the term Hit parade begins by saying it is a ranked list of the most popular recordings at a certain point in time, but subsequently states that through the late 1940s the term hit parade referred to a list of compositions, since “In those times, when a tune became a hit, it was typically recorded by several different artists.” The latter use of the term suggests that the Billboard Hit Parade charts from 1936 to 1939 may have only ranked songs, rather than individual recordings, according to their popularity. I’ve yet to find any of these early Billboard Hit Parade charts online.

In section 1.4 of the article Review of Irving Berlin: A Life In Song, by Philip Furia, by music theorist and historian David Carson Berry, published in the Volume 6, Number 5, November 2000 issue of the journal Music Theory Online, the authors says (link and italics added):

Beginning in 1935 (nearly three decades after Berlin’s first song), Your Hit Parade was broadcast on radio (and later on television); it offered a national survey, with chart positions based on various factors including sales of records and sheet music (although its evolving rankings formula was never clearly articulated). Thus, from 1935 onward, one can at least say that a song was number X according to that particular source. For songs released beforehand, however, there is no consistent way to derive such a ranking. Variety and other publications may provide ad hoc sales figures, or print very specific charts (for example, of record sales by a given company in a given market), but they offer nothing that would enable one to say, so generally, that a song was “number X” nationally.

From where did the national (US) chart positions for years prior to 1935 or 1936, that can now be found all over the web, come from? As outlined above, they sprang from the imagination of Joel Whitburn. There were no national charts during this era for best-selling or most popular records; therefore, no national chart positions. Why make them up?

Popular websites which routinely and extensively incorporate Joel Whitburn’s fabricated pre-1936 “chart” figures include:

- Wikipedia

- MusicVF.com

- JazzStandards.com

- TSort.info — via “charts” drawn from bullfrogspond.com, a site which is presently down

For a list of links to the aforementioned and other critical views of Joel Whitburn’s chart fabrication and misrepresentation of sources in the 1986 book Pop Memories 1890-1954: The History of American Popular Music, see the following Songbook page:

Regarding Whitburn’s takes on the popularity of the first three songs featured on this page, “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay,” “After the Ball,” and “Daisy Bell,” in the aforementioned 26 November 1989 review Tim Brooks wrote:

“After the Ball” (1892) is shown in Pop Memories as one of the biggest hits of the decade. The author, Charles K. Harris, spent the remainder of his long life loudly proclaiming what an enormous seller his song had been and how with it he had virtually invented Tin Pan Alley. Even his autobiography is titled After the Ball. Eventually others began to repeat his colorful stories. But (1) examination of contemporary references in musical and theater journals indicate that while the song was indeed popular in late 1892 and early 1893, it quickly faded and was equaled or exceeded by scores of later, less‑remembered tunes; and (2) it had virtually no impact on records. Another title that seems to have benefited from subsequent legend‑building is “Daisy Bell” (“On a Bicycle Built For Two”). There is little contemporary evidence that it was anything more than one of many passing popular tunes.

Clinging to legend and lore, Whitburn imagines specific recorded versions of both these songs as “number one on the charts” for months on end and places both among the top ten best selling records of the entire decade. He has since said that the songs must have been huge hits because they are mentioned in latter‑day books. This is exactly how false information spreads. An author should look to original sources, not secondary ones, to find out what actually happened.

Conversely, it should be noted, contemporary evidence suggests that “Ta‑Ra‑Ra‑Boom‑Der‑E” was a much bigger seller than either of the forgoing [sic] titles, at least on record. While it is listed in Pop Memories it does not place as high as the forgoing‑‑apparently because its author did not tell colorful stories about it and it therefore gets less space in modern anecdotal histories.

1891

Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay (traditional?)

On the origins of the song:

- mudcat.org thread — Origins: Ta-Ra-Ra Boom-De-Ay

- Wikipedia page “Background” section

- The black origins of Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay, at The Vapour Trail (bellanta.wordpress.com)

From the Wikipedia page on the song:

The song’s first known public performance was in Henry J. Sayers‘ 1891 revue Tuxedo, which was performed in Boston, Massachusetts. The song became widely known in the version sung by Lottie Collins in London music halls in 1892 [with new words by Richard Morton and a new arrangement by Angelo A. Asher].[1] The tune was later used in various contexts, including as the theme song to the television show Howdy Doody.

The song’s first known public performance was in Henry J. Sayers‘ 1891 revue Tuxedo, which was performed in Boston, Massachusetts. The song became widely known in the version sung by Lottie Collins in London music halls in 1892 [with new words by Richard Morton and a new arrangement by Angelo A. Asher].[1] The tune was later used in various contexts, including as the theme song to the television show Howdy Doody.

Background

The song’s authorship was disputed for some years.[2] It was originally credited to Sayers, who was the manager of the George Thatcher Minstrels; Sayers used the song in his 1891 production Tuxedo, a minstrel farce variety show in which “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay” was sung by Mamie Gilroy.[3][4] However, Sayers later said that he had not written the song, but had heard it performed in the 1880s by a black singer, Mama Lou, in a well-known St. Louis brothel run by “Babe” Connors.[1]

Stephen Cooney, Lottie Collins’ husband, heard the song in Tuxedo and purchased from Sayers rights for Collins to perform the song in England.[2] Collins worked up a dance routine around it, and, with new words by Richard Morton and a new arrangement by Angelo A. Asher, she first sang the song at the Tivoli Music Hall on The Strand in London in 1891 to an enthusiastic reception; it became her signature tune.[5] She performed it to great acclaim in the 1892 adaptation of Edmond Audran‘s opérette, Miss Helyett. According to reviews at the time, Collins delivered the suggestive verses with deceptive demureness, before launching into the lusty refrain and her celebrated “kick dance”, a kind of cancan in which, according to one reviewer, “she turns, twists, contorts, revolutionizes, and disports her lithe and muscular figure into a hundred different poses, all bizarre”.[6]

The song was performed in France under the title ‘Tha-ma-ra-boum-di-hé’, first by Mlle. Duclerc at Aux Ambassadeurs in 1891, but the following year as a major hit for Polaire at the Folies Bergère.[7][8] In 1892 The New York Times reported that a French version of the song had appeared under the title ‘Boom-allez’.[2]

Later editions of the music credited its authorship to various persons, including Alfred Moor-King, Paul Stanley,[9] and Angelo A. Asher.[10] Some claimed that the song was originally used at American revival meetings, while Richard Morton, who wrote the version of the lyric used in Lottie Collins’ performances, said that its origin was “Eastern”.[2][10] Around 1914 Joe Hill wrote a version which tells the tale of how poor working conditions can lead workers into “accidentally” causing their machinery to have mishaps.[11] A 1930s lawsuit determined that the tune and the refrain were in the public domain.[6]

_____________________

music boxes

Regina 15.5″ music box — plays Original Zinc Regina disc #1206

.

(below) 7 5/8″ Symphonion Style 10

_____________________

1892

After the Ball (Charles K. Harris) This song was the first to sell over a million copies of sheet music. The mass appeal of the song is generally given credit for jump-starting the American songwriting industry which had been in a dormant stage since the Civil War. Parlor Songs has a biographical sketch of Harris here: Chas. K. Harris “King of the Tearjerker“.

After the Ball (Charles K. Harris) This song was the first to sell over a million copies of sheet music. The mass appeal of the song is generally given credit for jump-starting the American songwriting industry which had been in a dormant stage since the Civil War. Parlor Songs has a biographical sketch of Harris here: Chas. K. Harris “King of the Tearjerker“.

From Wikipedia:

After the Ball is a popular song written in 1891 by Charles K. Harris. The song is a classic waltz in 3/4 time. In the song, an older man tells his niece why he has never married. He saw his sweetheart kissing another man at a ball, and he refused to listen to her explanation. Many years later, after the woman had died, he discovered that the man was her brother.

After the Ball became the most successful song of its era which at that time was gauged by the sales of sheet music. In 1892 it sold over two million copies of sheet music. Its total sheet music sales exceed five million copies, making it the best seller in Tin Pan Alley’s history.[1]

The following undated film short has Charles K. Harris himself introducing and singing his most popular song.

____________________

Daisy Bell (Harry Dacre) — The opening lyrics to the refrain,

Daisy, Daisy

Give me your answer, do

I’m half crazy

All for the love of you

are better known than the title. The song is sometimes referred to as “A Bicycle Built for Two” or “On a Bicycle Built for Two,” from the last line in the refrain:

Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do

I’m half crazy all for the love of you

It won’t be a stylish marriage

I can’t afford a carriage

But you’ll look sweet upon the seat

Of a bicycle built for two

Wikipedia, quoting American Popular Songs, David Ewen (1966):

“Daisy Bell” was composed by Harry Dacre in 1892. As David Ewen writes in American Popular Songs:[1]

When Dacre, an English popular composer, first came to the United States, he brought with him a bicycle, for which he was charged duty. His friend (the songwriter William Jerome) remarked lightly: ‘It’s lucky you didn’t bring a bicycle built for two, otherwise you’d have to pay double duty.’ Dacre was so taken with the phrase ‘bicycle built for two’ that he decided to use it in a song. That song, Daisy Bell, first became successful in a London music hall, in a performance by Katie Lawrence. Tony Pastor was the first one to sing it in the United States. Its success in America began when Jennie Lindsay brought down the house with it at the Atlantic Gardens on the Bowery early in 1892.

The most famous version of the song is that by the computer, Hal 9000, in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. A video creator posting a solo piano version (since removed) noted that there are virtually no well-known versions other than that by Hal 9000, unless it’s the version by the computer IBM 7094 which inspired that role.

Gerald Adams & Variety Singers — issued in 1931 on the 78rpm single Regal Zonophone G20854

From the site Dance Band Encyclopedia:

Gerald Adams was a trained singer (a tenor) who was called upon occasionally to provide vocals on dance bands recordings for house bands, though he was much more at home singing ballads than “pop” tunes. He recorded a handful of vocals for Stan Greening at Regal (issued as Lido Dance Orchestra or Raymond Dance Band) and also at Edison Bell with their house band.

.

.

Nat King Cole — released under the title “On a Bicycle Built for Two” on the 1963 album Those Lazy-Hazy-Crazy Days of Summer

______________________

The Cat Came Back (Harry S. Miller) — published in 1893

Selected recordings of “The Cat Came Back” are arranged on the following Songbook page:

- The Cat Came Back (Harry S. Miller)

Judging by the number of versions of “The Cat Came Back” available in online video libraries, many of them made recently, it appears to be remain very popular, especially as a children’s song. Although this is certainly the most well-known song written by Miller, he wrote numerous others including the following song, also from 1893.

____________________

Can’t Lose Me, Charlie (Henry S. Miller)

Wikipedia reports this as one of many Miller songs that have been lost, “along with their date of composition.” But they include the title in their songs published in 1893 and have a copy of the sheet music cover. I decided to do a bit of hunting to see if I might turn up a lyric if not the music.

Wikipedia reports this as one of many Miller songs that have been lost, “along with their date of composition.” But they include the title in their songs published in 1893 and have a copy of the sheet music cover. I decided to do a bit of hunting to see if I might turn up a lyric if not the music.

Update, 2 Jan 2011:

Here’s a link to the sheet music at Brown University, posted by Jim Dixon in a mudcat.org forum thread on the song.

Sheet music, from Brown University:

The full lyric is on the back cover, the last image on the right above. Note that the copyright, owned by the Chicago publisher Will Rossiter, is dated 1894 on the front cover (or does this date apply to Julie McKay’s “new Descriptive Song”) but 1893 on sheet 2 (first page of music), and also 1893 on the back cover. For easy readability, try three clicks on the gallery images above, and two clicks for the image below.

It wasn’t long before I came across a song by Leadbelly with a very similar title. Shortly afterward I found some relevant information at the Willa Cather Archives (http://cather.unl.edu). An April 5, 1894 entry by Cather in the “Amusements” section of the Nebraska State Journal comments briefly on a recent minstrel show in Lincoln (the state capitol) and gives the titles of a number of songs performed on the occasion, including You Can’t Lose Me Cholly. A footnote on the same page provides credits and publishing information on the song, as well as the first line of verse; it then offers an hypothesis on its subsequent evolution:

You Can’t Lose Me, Cholly: This song, “Can’t Lose Me, Charlie,” was composed by Harry S. Miller, with words by Richard Morton, and was published in Chicago in 1893. The verse begins, “I got a heap of trouble now.” The song appears to have passed into the folk repertory by the 1930s, with the title and first line of the chorus given as “You Can’t Loose-a Me, Charlie;” it was recorded by Leadbelly in 1934.

The footnote disagrees with the sheet music cover as to authorship. The cover has both words and music by Harry S. Miller. Miller had used the phrase “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay,” in the original lyric of The Cat Came Back in a deprecating reference to the big 1891 hit of the same title, which features, in the version made famous by Lottie Collins, a lyric by Richard Morton. Miller might have done something similar in this song, that is borrow a phrase from the lyric of another song by Morton, but I’m just speculating as to the reason for Morton’s inclusion as lyricist in the above quote.

_________________

You Can’t Lose-a Me, Cholly (traditional?)

A comparison of lyrics suggests that the song recorded by Leadbelly in 1934 under the title “You Can’t Lose-a Me, Cholly” is either derived in part from the song published in 1893 as “Can’t Lose Me Charlie,” with the songwriting credited to Henry S. Miller, or that both were in part derived from an earlier song. According to the folk song catalogue, ibiblio.org, John and Allan Lomax collected “You Can’t Lose-a Me, Cholly” from Leadbelly and identified it as a traditional song. Ibiblio also gives a related title (“rt”), “Down at Widow Johnson’s” (see update dated 4 August 2010 immediately below). Was Miller’s 1893 song adapted from a traditional?

Update, 4 August 2010:

Today I found partial sheet music for the turn of the century song “Down at Widow Johnson’s”, a title which is identified by ibiblio.org (see previous paragraph) as related to the song Leadbelly recorded in 1934 as “You Can’t Lose-a Me, Cholly.” The publication titled The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore: Vol. V — The Music of the Folk Songs (1977) ed. Newman I. White, has a page of sheet music, with words, for what appears to be the first 17 measures of the song — see here Brown collection, p. 471.

According to the introductory notes on the sheet music page, the source of this transcription (presumably by the author Brown) was a performance by Bascom Lamar Lunsford as heard by the author in Turkey Creek, Buncombe County, [NC] in 1902. The note also mentions that Lunsford told the author that he had learned the tune from Lula Black that same year, and that Lunsford sang the tune again for the author in 1945 (43 years later) “to get a better recording.”

The verse portion of Lunsford’s “Down at Widow Johnson’s” is virtually identical to the third verse of the Miller’s “Can’t Lose Me, Charlie” (See the lyric in the sheet music from Brown University, above).

In a thread, titled “Lyr Add/Origin: Can’t Lose Me, Charlie,” at the forum Mudcat Cafe, lyrics for both the 1893 song by Henry S. Miller and the Leadbelly song are provided by guest Bob Coltman. In a post dated 03 Jul 10 – 08:11 PM, Coltman entertains my speculation as to the origin of the title, but considers my suggestion that Miller may have adopted it from the folk tradition “a long shot, but it’s possible given Miller’s apparently thorough immersion in African American dialect of the time.” My reply is that he may be right, but how on earth did the Lomaxes miss the Miller connection to Leadbelly’s “traditional.” One assumes that the Lomaxes had substantial reason for designating the Leadbelly song as they did. If the Lomaxes had traced the origin of the Leadbelly number to 1893 and noticed the resemblance to Miller’s song, I can’t imagine how they would have or could have identified it a traditional, unless they had evidence of precedents.

I’ve not yet discovered what evidence the Lomaxes used to determine that “You Can’t Lose-a Me, Cholly” should be classsified as a traditional, but given this designation, if we find significant lyrical connection between the song published by Miller in 1893 and the various Leadbelly versions, would this not suggest that Miller’s song might have also derived from tradition?

The portion of the 1902 version given in the Google Books extract more closely resembles a verse and the chorus or refrain of the Miller lyric, which can be seen in full on the back (fourth) page of the sheet music I’ve provided above, than it does any part of either of the Leadbelly versions below. Virtually the same name for the nagging entity quoted in the refrain is used in “Down at the Widow Johnson’s” and the Miller lyric, “Hannah” in the former and “Hanner” in the latter. In the third section of the Miller lyric the widow is referred to as “Widow Johnson,” the same name used in the title and first line of the 1902 version. Conversely, Leadbelly doesn’t mention a widow at all in the recordings of the song by him that I’ve heard. The female or females referred to in the Leadbelly versions are identified variously as “Willie Winston,” “the gal,” or “a yaller [yellow] gal.” On the other hand, the 1902 lyric has her saying, “You can’t fool me…” instead of “You can’t lose me…” as found in the Miller original lyric and in the words sung by Leadbelly.

Leadbelly — three undated recordings

The first version below contains the following peculiar lines (Another version, previously included here, has “You” instead of “We” beginning the third line.).

Me and my buddy went down the road

Trying to get the money to buy a goat

(We got to have a goat to drink water out of)

The phrase “We got to have” is a colloquial version of “We’ve got to have,” which is the equivalent of “We must have.” They intend to acquire some money so that they may purchase a “goat,” which will carry their drinking water, and from which they will drink the water. The word “goat” here is likely a short-form word for goatskin canteen (aka bota bag, wineskin).

1

.

2

.

3

____________________

1894

The Sidewalks of New York (Charles B. Lawlor, James W. Blake)

Excerpts from the wikipedia article:

The tune, a slow and deliberate waltz, was devised by Lawlor, who had been humming the tune while stopping by the hat store where Blake worked. As the two became increasingly enthusiastic about the song, they agreed to collaborate, with Lawlor putting the tune to sheet music and Blake creating the lyrics.[1] The words of the song tell the story of Blake’s childhood, including the friends with whom he played as a child, namely Johnny Casey, Jimmy Crowe, Nellie Shannon (who danced the waltz), and Mamie O’Rourke (who taught Blake how to “trip the light fantastic,” an extravagant expression for dancing). The song is sung in nostalgic retrospect, as Blake and his childhood friends went their separate ways, some leading to success while others did not (“some are up in ‘G’ / others they are on the hog”).

The tune, a slow and deliberate waltz, was devised by Lawlor, who had been humming the tune while stopping by the hat store where Blake worked. As the two became increasingly enthusiastic about the song, they agreed to collaborate, with Lawlor putting the tune to sheet music and Blake creating the lyrics.[1] The words of the song tell the story of Blake’s childhood, including the friends with whom he played as a child, namely Johnny Casey, Jimmy Crowe, Nellie Shannon (who danced the waltz), and Mamie O’Rourke (who taught Blake how to “trip the light fantastic,” an extravagant expression for dancing). The song is sung in nostalgic retrospect, as Blake and his childhood friends went their separate ways, some leading to success while others did not (“some are up in ‘G’ / others they are on the hog”).

Though the song achieved cultural success shortly after its release, the two authors earned only $5,000 for their efforts. Lawlor died penniless in 1925, while Blake fell ill and died in 1935, their song reputedly having sold 5,000 copies a year by the time of Blake’s passing.[3]

The song…was once considered a theme for New York City. Many artists, including Mel Tormé, Duke Ellington, Larry Groce and The Grateful Dead, have performed this song. Governor Al Smith of New York used it as a theme song for his failed presidential campaign in 1928. The song is also known under the title “East Side, West Side” from the first words of the chorus.

George J. Gaskin — recorded in New York City on 29 October 1895; issued on 7″ Emile Berliner record

.

Shannon Quartet — first issued in 1928, according to the video provider

_______________________________

1895

The Band Played On (John F. Palmer, Charles B. Ward)

Casey would waltz with a strawberry blonde

As the band played on;

He’d glide ‘cross the floor with the girl he adored

As the band played on;

Well, his brain was so loaded

It nearly exploded

The poor girl would shake with alarm;

He’d ne’er leave the girl with the strawberry curl

As the band played on.

The song has become a pop standard with many recordings made. It was also featured in many films, including Raoul Walsh’s The Strawberry Blonde, where it was performed by James Cagney and Rita Hayworth, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train. One of the most famous recordings, by Guy Lombardo’s orchestra, was made on February 26, 1941. – adapted from the Wikipedia page

____________________

Dan Quinn – released in 1895 on the cylinder Columbia 2045

.

The Hoosier Hot Shots — recorded on 5 June 1941; issued on the 78 rpm single OKeh 06273, as the B-side of “The Hut-Sut Song (A Swedish Serenade)”

_______________

See the separate feature page:

___________________

1896

A Hot Time in the Old Town (m. Theodore August Metz, w. Joe Hayden)

Excerpts from the Wikipedia article on the song:

A Hot Time in the Old Town is a ragtime song, composed in 1896 by Theodore August Metz with lyrics by Joe Hayden. Metz was the band leader of the McIntyre and Heath Minstrels.

A Hot Time in the Old Town is a ragtime song, composed in 1896 by Theodore August Metz with lyrics by Joe Hayden. Metz was the band leader of the McIntyre and Heath Minstrels.

The song was a favorite of the American military at the turn of the 20th century, particularly during the Spanish-American War and the Boxer Rebellion.[3]

lyric:

Come along get you ready wear your bran, bran new gown,

For dere’s gwine to be a meeting in that good, good old town,

Where you knowed ev’ry body, and they all knowed you,

And you’ve got a rabbits foot to keep away the hoodo;

Where you hear that the preaching does begin,

Bend down low for to drive away your sin

And when you gets religion, you want to shout and sing,

There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight, my baby.

[refrain]

When you hear dem a bells go ding, ling ling,

All join ’round and sweetly you must sing,

And when the verse am through,

In the chorus all join in,

There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight.

There’ll be girls for ev’ry body in that good, good old town,

For dere’s Miss Consola Davis an dere’s Miss Gondolia Brown;

And dere’s Miss Johanna Beasly she am dressed all in red,

I just hugged her and I kissed her and to me then she said

Please oh, please, Oh, do not let me fall,

You’re all mine and I love you best of all,

And you must be my man, or I’ll have no man at all,

There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight, my baby.

(Repeat refrain)

Dan W. Quinn — recorded in 1897; Emile Berliner record 527

.

Bessie Smith, accompanied by some members of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra (see notes by the provider) — 1927

______________________________

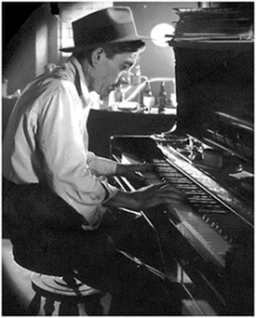

1899

From Wikipedia, adapted:

Maple Leaf Rag (Scott Joplin) is an early ragtime composition for piano by Scott Joplin. It was one of Joplin’s early works, and is one of the most famous of all ragtime pieces, becoming the first instrumental piece to sell over one million copies of sheet music.

Maple Leaf Rag (Scott Joplin) is an early ragtime composition for piano by Scott Joplin. It was one of Joplin’s early works, and is one of the most famous of all ragtime pieces, becoming the first instrumental piece to sell over one million copies of sheet music.

In 1916, Joplin recorded the Maple Leaf Rag on a piano roll on the Connorized and Aeolian Uni-Record labels, along with other ragtime pieces: “Something Doing”, “Magnetic Rag”, “Ole Miss Rag” (composed by W.C. Handy), “Weeping Willow” and “Pleasant Moments: Ragtime Waltz”.

Audio files from Internet Archive (archive.org):

Scott Joplin — piano roll, recorded in 1916 by the composer Scott Joplin for Aeolian Uni-Record

Ogg Vorbis (1.7 MB) — https://archive.org/details/MapleLeafRag

.

U. S. Marine Band — 1906 recording

MP3 format (1.1 MB)

____________________

My Wild Irish Rose (Chancellor Olcott)

My Wild Irish Rose (Chancellor Olcott)

Chancellor “Chauncey” Olcott (July 21, 1858 – March 18, 1932) was an American stage actor, songwriter and singer.

Born in Buffalo, New York, in the early years of his career Olcott sang in minstrel shows. Lillian Russell played a major role in helping make him a Broadway star. Amongst his songwriting accomplishments, Olcott wrote and composed the song “My Wild Irish Rose” for his production of “A Romance of Athlone” in 1899. Olcott also wrote the lyrics to “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” for his production of “The Isle O’ Dreams” in 1912.

A cyclinder dated early 1910s by the provider. The tenor is Walter Van Brunt.

________________________________

* The article at timbrooks.net is dated November 26, 1989. However, the page URL bears the date 1990, and a page bottom note following the review and its ten footnotes indicates that the page, which consists almost entirely of the review, was “last modified on November 5th, 2011.”

Aug 08, 2010 @ 10:56:03

On the “you’ve Been a Good Old Wagon” question: the two versions on this great site (Ben Harney, and the piano instrumental by Jamie Levac) are definitely not the same song as “Youve Been … Wagon” by Bessie Smith. They are a variant version of the song that John and Alan Lomax published in one of their earlier books, where it’s titled, if I remember right, “Sugar Babe”, which is a variant (or maybe the original) version of “Crawdad Hole” (…”you get a line and I’ll get a pole this mornin’/you get a line and I’ll get a pole this evenin’/you get a line and I’ll get a pole/we’ll go down to the crawdad hole/this mornin’ this evenin’ so soon …” “Sugar Babe” used the same tune, and includes the great verse: Put your mind at ease and let the world go by, Sugar Babe/Put your mind at ease and let the world go by, cause your body’s gonna swivel when you come to die, Sugar Babe.”

The Grateful Dead did a damn good rocked out version of it, with some tasty transposed chords; I think Jesse Colin Young did a fine up-tempo version of it too — the one in the Lomaxs’ book is my favorite version (my mother, a singer, loved it and sang it with me, sixty-some years ago). The first verse goes: Shoot your dice and have your fun, Sugar Babe/(repeat)/ Shoot your dice and have your fun, run like hell when the police come, Sugar Babe [or: Sugar, Ba-a-by Mine]

My guess is that the line “You been a good old wagon but you done broke down” was picked up from the Ben Harney version — or some other source in earlier circulation — and then became the title line and “hook” of a new song, with new melody and other lyrics, that new one being the song that Bessie Smith recorded.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aug 08, 2010 @ 15:36:52

Hi Mike, Thanks for the information on the origins of “Good Ol’ Wagon”/”Sugar Babe.” I will definitely check out the Grateful Dead and Jesse Colin Young versions that you refer to. I had skipped the tune entirely in my Bessie Smith features because of the question of authorship. The history of folk music is rather out of my realm, though I occasionally get caught up in tracing the evolution of a song. See, for example, my amateur analysis of the Can’t Lose Me, Charlie (Henry S. Miller)/ Down at Widow Johnson’s (traditional?)/ You Can’t Lose Me, Cholly (Leadbelly) connection (above, this page). Just scratching the surface of these histories really — Cheers, Jim

LikeLike

Nov 28, 2013 @ 19:28:58

Mike,

Regarding Harney’s “Good Old Wagon” being a variant of the folk songs “Sweet Thing” and “Crawdad Hole”, see my response within the page.

LikeLike

Jan 01, 2014 @ 02:43:05

Today, the article on the song “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon…” previously featured in this page was relocated to a separate page, here:

“You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You’ve Done Broke Down“

LikeLike

Oct 17, 2010 @ 16:42:12

To Mike Mason,

Sugar Babe, It’s All Over Now (traditional) — Mance Lipscomb, live (date unknown)

.

The video below contains a recording by Jesse Colin Young of “Sugar Babe,” a remastered version according to the provider, of a track from Young’s 1975 album Songbird, Warner Bros. Records BS 2845. The labels on each side of the album bear the note “All selections written by Jesse Colin Young.” The song appears to be entirely unrelated to the traditional “Sugar Babe” that is related to the traditional “Crawdad,” although it might have been influenced by the different traditional “Sugar Babe, It’s All Over Now” (aka “Sugar Babe”) that was recorded by Mance Lipscomb (1960), Mark Spoelstra (1963), and Tom Rush (1966), among others. See an undated performance by Mance Lipscomb in the video above.

In the slide show of the following video, the provider uses the label of a 1960 single by Gene & Eunice issued by Case Records. The credit on the label, “D. Frazier,” refers to songwriter and musician, Dallas Frazier, born in 1939. Frazier did indeed write a song called “Sugar Babe” which was recorded by Gene & Eunice (Case 1007, b/w “Let’s Play the Game,” issued in 1960), and The Mavricks (1961), but this is not the song recorded by Young.

Regards,

doc

LikeLike

Oct 02, 2019 @ 22:05:17

That remains my opinion. However, I’ve recently discovered that an earlier recording of “Sugar Babe” by the Youngbloods, featuring Jesse Colin Young, is credited on the labels of various early American, German, UK, Australian, and Canadian editions of the 1967 Youngbloods album Earth Music to “Young-Lomax,” and even a 2009 reissue of the album credits the songwriters as “Young-Lomax.” The c.1967 Youngbloods recording of the song is not significantly different, with respect to music or lyrics, from the Jesse Colin Young recording released on Songbird in 1975, although the tempo is considerably slower in the latter.

LikeLike

Aug 25, 2012 @ 09:20:32

where i can listen this all songs? pls help me thanks

LikeLike

Aug 25, 2012 @ 14:37:39

Melvin,

Try some of the external links on this page audio file sites, external. Among the listed links, those especially useful for audio files of the 1890s might include:

Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project

100 Years of Jazz and Popular Music Index Page: 1850-1959

Midi files and lyrics:

Music from 1866-1899 (Public Domain Music, pdmusic.org)

Minstrel Songs Old and New (pdmusic.org)

Parlor Songs Academy, site index

Popular Songs in American History (contemplator.com) 17th century to c. 1900

LikeLike

Aug 28, 2012 @ 08:10:24

thank you so much doc! i was able to listen to the songs already but is there any way that i can listen to the songs with vocals?? because if am not mistaken those were all instrumental, right? thanks in advance!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aug 28, 2012 @ 15:50:15

Melvin,

Hi. Not sure what you are referring to. Instrumentals where? You may be listening to audio files on one page and leaving a comment on another. You are commenting on the page 1890-1899 selected hits and standards. This page does not have many instrumentals. Please try to explain the issue more thoroughly.

LikeLike

Jan 26, 2013 @ 09:51:34

Here is a medley of waltzes by the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra. I have sent them a message asking this question but they don’t seem to want to answer customer inquiries.

https://www.box.com/s/vho26vyxzeehayfc8a4o

I have identified most of these songs, but there are 2 that I can’t place:

1. The Bowery

2. Sidewalks of New York

3. Sweet Rosie O’Grady

4. Daisy Bell

5. ????

6. Little Annie Rooney

7. ???

8. The Band Played On

9. After the Ball

Do you recognize songs 5 and 7?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 26, 2013 @ 23:24:56

I’m out of my element in music of this era. I thought number 5 might be Comrades (1887) because I’d heard it in a Victor Medley not long ago and found it melodically similar to The Band Played On. I noticed the similarity in this medley as well. Had no idea on number 7.

Then I did a Youtube search on the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra medley and found that there are presently numerous videos containing it posted there. Some of them indicate that the track is the soundtrack (or part of the soundtrack?) of the Main Street USA attraction at Disneyland Resort Paris. Here’s the URL of a video where I found an answer to your question: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMxWMzTIL1o. In the top comment, directly below the video, gene1qw2 identifies the songs as follows:

The Bowery

The Sidewalks of New York

Sweet Rosie O’Grady

Daisy Bell

Comrades

Little Annie Rooney

She May Have Seen Better Days

The Band Played On

After The Ball

LikeLike

Jan 27, 2013 @ 07:22:50

Thanks. I don’t know why I didn’t think of searching on You Tube for a video with that title. Sometimes it takes more heads than one. I’m making a new video with images and the lyrics to each song, rather than the single still on the existing video. But, without the lyrics to those two songs, I wasn’t able to finish it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jun 05, 2013 @ 20:27:42

Im trying to find a song, its sung in rounds, from this era or nearabouts, either called ‘why dont you get lost?’ ,main chorus is that sentence. It has male n female singers, like a humorous argument between married couple? Thanks for informative page. Mish

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jun 06, 2013 @ 06:01:06

From which era? 1890s or thereabouts?

LikeLike

Jun 06, 2013 @ 06:14:26

Yes, somewhere between then and the forties, but i think earlier, i used to listen through a person on myspace called old masters, but they have since disapearred, unfortunately. I wish i hadve noted, because it was quite humorous, cudve even been vaudville…its like a couple arging, n saying what a pain each other is, then they say, well why dont you get lost? Thats the repeated line. Be so grateful if you or anyone else could put me in right direction. The lyrics r just really great. i think the myspace person was some digital remastering place in u.s., unfortunately no longer active but im sure was legitimate company or group. Thanks again

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jun 06, 2013 @ 06:21:14

There’s a 1932 song titled Why Don’t You Get Lost? credited to J. Russell Robinson, Phil Wall, and Robert Effros. I haven’t heard it done as a mixed duet, but I can imagine it being adapted to that purpose. Not sure what you mean by “sung in rounds.” Do you mean as a round? It reminds me of the mixed duet song “I’m Gonna Wash My Hands of You,” recorded by Ambrose (1934) and others.

Why Don’t You Get Lost? (J. Russell Robinson, Phil Wall, and Robert Effros)

Chick Bullock and His Levee Loungers — That’s the name of the band on the label displayed in the video, the catalog number of which indicates that it’s the B-side of Banner 32659. According to The Online Discographical Project (78discography.com), the side was recorded on 13 May 1932 and issued on the 78 rpm single Banner 32659, c/w “Goofus.” However, 78discography.com credits both sides of Banner 32659 to the band Gene’s Merrymakers. If this is a mistake, then it might have in part been due to the fact that the same two sides were issued on Oriole 2631, with the band credited as “Gene’s Merrymakers.”

LikeLike

Jun 02, 2016 @ 21:36:24

Another recording of “Why Don’t You Get Lost?” (J. Russell Robinson, Phil Wall, Robert Effros)

Calloway’s Hot Shots (aka Roane’s Pennsylvanians, Snooks and His Memphis Stompers) — recorded on 2 June 1932 (Victor matrix BSHQ-72839) and issued on the 78 rpm single Victor 24037, b/w “Sweet Birds” — also issued on Bluebird B-5108, and Sunrise S-3191, with “Sweet Birds” on the other side in each case.

LikeLike

Mar 05, 2014 @ 00:21:20

Thanks for posting! My grandpa, Bob Effros & Phil Wall composed and played trumpet here. I still have the original record!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 05, 2014 @ 16:54:23

LikeLike